At 10 AM, beams of radiant gold light are breaking through the cloud cover above the wooded summits of the Alishan mountain range in southwest Taiwan. I am traveling via a vintage steam locomotive, and much remains unchanged from when this train made its inaugural journey through these pine-filled valleys back in 1912.

Outside my window, dense groups of hinoki — also called Japanese cypress — form a pathway lined up like an honor guard. Their twisted yet rigid trunks compete for room alongside bamboo, which holds great value for the indigenous Tsou people and serves various purposes ranging from building structures to making handicrafts.

For better or worse, this area has been defined by the

Japanese

Those who came here following the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895 included forestry specialists sent to the area near the start of the twentieth century. These experts verified the existence of an extensive population of conifer trees in the region.

In 1906, the Japanese corporation Fujita Group embarked on constructing a railroad, driven by their strong desire to foster a forestry sector based on the extensive forests of cedar and cypress trees covering these mountainous regions.

However, achieving this was not simple. The construction was halted in 1908, leading to

Taiwanese

the government assumed control of the project, and in 1912, the initial steam locomotives began running on the tracks.

Thrumming along newly refurbished rails

Today, as I traverse the woods of Alishan National Scenic Area along the newly refurbished 71-kilometer route,

railway

(resuming full operations in 2024), it becomes clear why Japan acknowledged their loss. This path features numerous hairpin turns, 77 bridges, and 50 tunnels – including one that now showcases gigantic sunflower murals.

Shay locomotives manufactured in the US were brought in to facilitate the transportation of substantial cargo—thousands of tons of wood headed for Taiwan’s harbors—but various challenges proved more difficult to surmount. The area frequently faced destruction from typhoons, earthquakes, and landslides, and building the initial railroad was an impressive engineering accomplishment that demanded extensive labor.

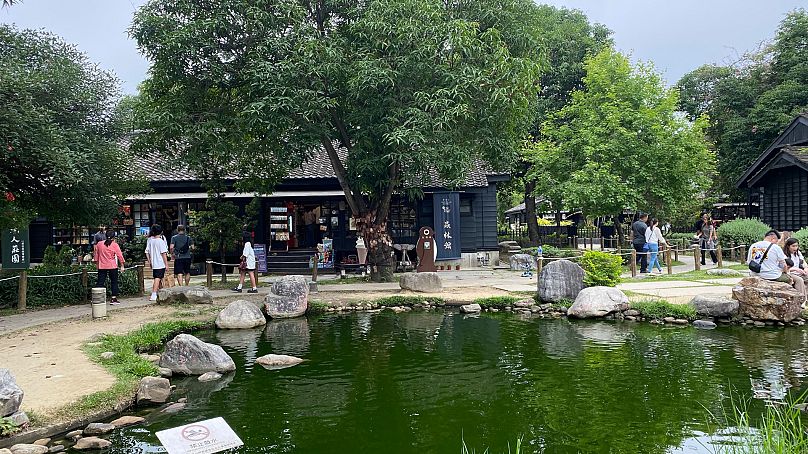

A significant number of these employees resided in Chiayi, a modest city influenced heavily by the lumber sector. This town serves as the departure spot for the heritage railroad, and presently, one of its principal draws is Hinoki Village—a grouping of low-set wooden bungalows constructed originally to serve as lodging for staff working with the railways and forests. Today, these same bungalows function as accommodations.

souvenir

stores offering cedarwood cutting boards and locally-grown oolong tea.

Sadly, the railway ground to a halt in the 1960s as the forestry industry declined. Occasional services still ran, but in 2009, Typhoon Morakot hammered the final nail in the coffin, prompting the closure of a railway line already in desperate need of some serious TLC.

The railway serves as a ‘living history of Taiwan.’

The workforce responsible for reviving this railroad in 2024 may not reside in Hinoki Village, yet their dedication is equally profound as that of its former inhabitants.

All those engaged in its restoration, be they the station masters stationed at some of the track’s loneliest stops or the engineers who manually installed segments of railway in hard-to-reach areas, share this viewpoint. It was not just about swapping out a handful of sleepers.

Mr. Shen Yi-Ching, who leads the Safety Management Division, explains, “The Alishan Forest Railway is more than just a railway; it serves as a vivid chronicle of Taiwan’s past. Established during Japan’s rule for logging purposes, this railway facilitated the movement of wood from these valuable forests. Over time, settlements, businesses, and distinctive cultural practices emerged alongside it.”

Moreover, this cultural aspect is celebrated by the railway through various means. Some compartments are paneled with aromatic cedarwood, while many stops along the way mirror the ambiance of sacred woodland shrines.

As we approach, I observe the conductor leaning out of the window and handing a big token, connected to a length of rope, to the station master.

train

When it departs, another token is returned to the conductor. This practice dates back to the railroad’s prime era and serves as proof that the train was authorized to travel over the preceding stretch of track and now has clearance to move forward to the subsequent segment.

Tourists have replaced cargo

Train stations like Jiaoliping, nestled between cedar-covered mountains and a track-side, lantern-lit temple, remain impeccably tidy.

All too often,

railways in Europe

turn into disposal sites for empty bottles, cans, and various debris. However, in this location, even small pieces of trash are swiftly picked up by residents from nearby areas who view the railway as crucial infrastructure. They often organize cleanup events to keep the area tidy.

The trains rumbling down this track weren’t solely used for transporting timber—they also ferried provisions and mail, linking residents to the broader world. Nowadays, the main cargo consists of visitors—an asset of equal worth. Numerous stops now serve dual purposes as starting points for various excursions.

hikers

eager to discover the paths meandering through Alishan’s mountainous terrain, illuminated with fireflies.

The lumberjacks and railway workers who used to stop at these stations for resting and refueling spots have been substituted with visitors queuing up at food stands to enjoy the bento boxes that were previously consumed by those working along the rail lines. I suggest trying some turkey rice (a local specialty here in this region of Taiwan) accompanied by a mug of oolong mountain tea (gāoshān chá).

Artifacts from the railroad’s prime time are always within reach. You can find old corroded fire-fighting tools that were utilized by workers to douse flames sparked by passing trains. For instance, Ruan Wen-An, residing beside the diminutive Dulishan railway station, eagerly shares with travelers an apparatus previously belonging to his grandfather.

At Fenqihu Station, ancient tools are showcased. This location features a grand wooden locomotive shed that has been converted into an exhibit area, allowing guests to explore the railroad’s past.

Dawn breaks over Taiwan’s highest summit

Many individuals consider the ultimate stop to be Alishan Station, situated 71.4 kilometers away from Chiayi. However, the brief yet delightful Zhushan Line, added in 1984 as an expansion, has also become part of the railroad narrative. This particular segment stands out as the sole addition made to the Alishan Forest Railway following World War II.

After reaching Alishan Station one day earlier, I head back to catch what they call the sunrise train for a half-hour trip to Zhushan Station. Situated at an altitude of 2,451 meters, this station stands as Taiwan’s highest railway stop. Following extensive refurbishment in 2023, it now boasts a grand curved roof designed like intertwined ribbons, along with design features that mirror the frequent cloud cover enveloping the nearby mountain summits.

The natural world has also influenced its structure; at the front, a large red cedar emerges through a specially crafted opening in the ceiling. This reflects a Taiwanese interpretation of mid-century modern architecture similar to those found in Palm Springs, where round apertures were often created for palm trees. Additionally, nature dictates when you can leave, as these timings vary based on sunrise each day. The scheduled departure times are shown on signs at the platforms, which require manual updates.

A

train

The worker informed me that even though this specific trip lasts only 30 minutes, it produces comparable revenue to the revived Alishan Forest Railway. This occurs because each morning, visitors rush to catch the train so they can witness the sunrise over the far-off mountains at an observation spot near Zhushan Station. Among the numerous natural attractions visible is Taiwan’s highest peak, Yushan (Jade Mountain).

The Alishan Forest Railway has genuinely weathered the passage of time, and it’s appropriate that much of its rejuvenation was accomplished manually rather than with machines. This effort represents a labor of devotion, and recently faced an unforeseen challenge, successfully overcoming it with great distinction.

A short time following its launch in July 2024,

Typhoon Gaemi

The typhoon swept across Taiwan, causing landslides that led to the closure of the railway for track clearance. However, unlike the storm, which ultimately determined its outcome in 2009, the railway suffered minimal damage and reopened just a month later—a testament to this cedar-fragranced triumph’s enduring presence.

Leave a Reply